|

|

As Michael Syrotinski wrote of Chagall's collaborator in the creation of this work, "It's difficult to overstate the importance of Jean Paulhan's role in French literature in the first half of the twentieth century, and the influence he wielded. He was closely involved with the leading literary review in France, the Nouvelle Revue Française, from 1920 to his death in 1968, and the director of the review during its illustrious interwar years. His position at the heart of the French literary scene, along with the many other associated editorial activities through which he nurtured and published the cream of a generation of writers, earned him the reputation as the 'grey eminence' of modern French literature.

His own texts are less well-known and certainly underappreciated, even in France, and this is perhaps a consequence of his legendary discretion and self-effacing modesty. His writing is at last beginning to attract the readership and the critical attention it deserves, as evidenced by the publication of his voluminous correspondence with many of the writers he became close friends with, a new seven-volume edition of his complete works (to appear with Gallimard), and more and more of his works, such as The Flowers of Tarbes, coming out in English translation. The Flowers of Tarbes is the text he is probably most associated with, but he was an extremely eclectic figure, by turns an anarchist, a short story writer, a mystic, a literary critic, an art lover, and a political polemicist. He loved all sorts of games, including the games one plays with language, and this comes through in the playfulness of his writing and thinking generally.

He was extremely well acquainted with the intellectual and political developments of his time, such as Saussurean linguistics, Freudian psychoanalysis, Marxism, German philosophy, ethnology, and phenomenology, and was as free-ranging and open-ended in his philosophical references (including, for example, Duns Scot, Vailati, Lao-Tseu, and the Ancient Greeks) as he was in his literary allusions. In fact he often went against the grain of prevailing opinion or ideology, with a certain calculated perversity, famously defending blacklisted collaborationist writers in the literary purge after the Second World War, when he had been one of the most prominent of Résistants during the war. As politically dubious as it may appear, Paulhan's polemic in fact argues passionately in favour of the need to respect democracy at a very fundamental level. People are now beginning to understand the originality of his thinking about the relationship between language, meaning, political action, and historical event, as well as its relevance to contemporary questions of political philosophy and literary theory.

Paulhan was also one of the champions of Cubist painting and of informel artists such as Fautrier and Dubuffet, and wrote several books on modern art. For him, it represented in many ways an aesthetic version, and an intensely successful one at that, of the immediacy and purity of expression he sought for so long in the literary and linguistic domain. It has been said about Paulhan that even though he was writing in the midst of the modernist revolution in art and literature, his thinking and writing belong more properly to the postmodern era.

Paulhan's focus on the rhetorical dimension of literature has led to the view of his work as prefiguring literary critics such as Gérard Genette, Roland Barthes, Paul de Man and Jacques Derrida. It is certainly true that Paulhan shared with both de Man and Derrida a keen attention to the epistemological and ethical consequences of taking the rhetorical uncertainties of language and literature seriously."

-- Michael Syrotinski (21/03/2006)

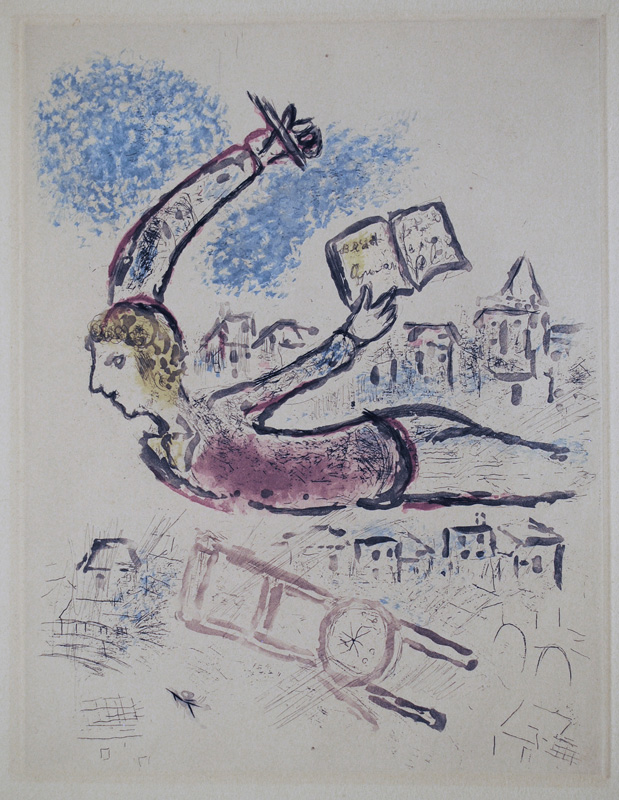

In De Mauvais Sujets, the narrative is a stream of consciousness within the mind of a young boy, worrying about appropriate subjects for his required essays in his French class at the same time that he is trying to find his own place within the Cartesian philosphical tradition (I think therefore I am) he is being taught and failing rather desperately: "La premiere fois, ç'a été vers l'age de dix ans, et ce n'était pas un découverte joyeuse, non. La voici: C'est que j'étais bête. Bête, ou, plus exactement vide: la pénsée ne me venait pas. Il s'agissait d'une panique, plus encore que d'une découverte, et je désespérais parfois de me corriger." (p. 9: The first time, it was about the age of 10 years old, and it was not a happy discovery, no! Here it is: I was a beast. A beast, or, more precisely empty: thought did not come to me. I panicked [i.e. fell into the state of total passionate existence in which Pan's followers dwell], all the more so for this discovery, and I despaired of ever correcting myself"). To take the place of reason, he tries to substitute the imagination: "Mois, j'étais jusque-là comme un enfant qui vient d'entendre ou d'imaginer quelque nouvelle dont il s'enchanté" (p. 40: Myself, I was until then like a child who has come to understand or to imagine something new with which he is completely enchanted) .

The etchings for De Mauvais Sujets, Chagall's first color etchings not using pochoir, were executed by Chagall in 1958; De Mauvais Sujets was issued in an edition of 10 portfolios on Japon Nacré, signed and numbered from A/J to J/J, 112 portfolios printed on velin d'Arches, each of which were numbered. In addition, there were 16 portfolios hors commerce for collaborators in the production numbered from I-XVI, and 25 portfolios for the artist numered from A to Y. Our impressions came from portfolio Q. The work was published by Les Bibliophiles de l'Union Françcaise in Paris. The color etchings were printed by Jacques Frélaut and Roger Lacourière. Because the work was available only to this small club of lovers of fine books, it is vcry rare to find one on the market.

Bibliography: Patrick Cramer, Marc Chagall: The Illustrated Books (Geneva: Patrick Cramer Publisher, 1995); E. W. Kornfeld, Verzeichnis der Kupferstiche, Radierungen, und Holzschnitte. Band I: Werke 1922-1966 (Bern: Verlag Kornfeld und Klipstein, 1970); Roger Passeron, Maîtres de la Gravure: Chagall (Paris: Bibliothèque des Arts, 1984); Charles Sorlier, Le Livre des Livres / The Illustrated Books (Monte Carlo: Editions André Sauret, 1990). Cramer and Kornfeld illustrate all ten of the color etchings, Sorlier illustrates three, andd one is included in Passeron.

|

|

|

|